The first three patients have undergone revolutionary brain surgery in a bid to treat the chronic pain they have experienced since suffering a stroke.

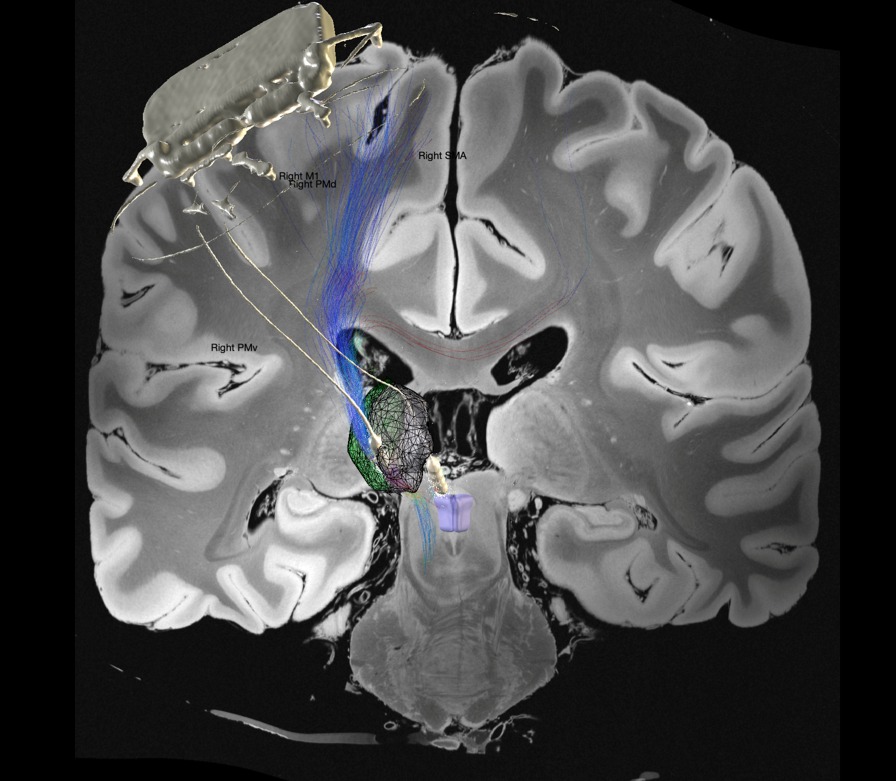

A research study by Oxford neurosurgeons and engineers is trialling whether deep brain stimulation (DBS) – delivering an electrical pulse into affected areas of the brain – can help to relieve central post-stroke pain (CPSP).

Severe, refractory CPSP, which is experienced by one in 12 stroke patients, is caused when the stroke affects the areas of the brain and central nervous system that process pain signals from the body.

CPSP can be disabling for those affected by it, and for some patients it does not respond to the current best medical treatment.

The EPIONE study, which is investigating whether DBS could be effective in treating CPSP, is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Oxford and Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centres (BRC).

DBS works by delivering a gentle electrical stimulation directly to specific brain areas through thin electrode wires. The level of stimulation can be adjusted depending on how it affects symptoms, meaning it can be tailored to each individual.

Alex Green, Professor of Neurosurgery, who is leading the study, said: “DBS has been used to treat other conditions, such as tremors in Parkinson’s patients, and has even been used to tackle pain in specialist clinics. However, there is not enough high-quality evidence that DBS works reliably for pain in CPSP to justify its routine use in the NHS.”

The EPIONE study team will carry out a randomised study in 30 patients with CPSP who will receive treatment from a DBS device called a Picostim®-DyNeuMo. The results of this study will inform whether this treatment could be delivered by the NHS in future.

“Once the clinical team are happy that the patient has recovered well from the surgery, we will adjust the DBS settings to achieve pain relief. We will then compare the response to an ‘on’ setting to an ‘off’(called pseudo-on because it still drains the battery). The order of the two settings will be decided at random before the device is switched on. This will allow us to fairly assess which of the settings is most effective at treating CPSP in each participant,” Professor Green explained.

The Picostim-DyNeuMo DBS system is a novel research platform and is the brainchild of Professor Tim Denison at the University of Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science. The aim of the trial is to develop the device in parallel with clinical testing. It contains novel features that can use signals such as brain recordings to automatically adjust stimulation (so called ‘closed loop stimulation).

Professor Denison is also pioneering the use of ‘circadian stimulation’ – adjusting the stimulation depending on time of day. The device is manufactured by Amber Therapeutics – a University of Oxford start-up company.

The operation involves the removal of a small amount of skull, to allow the DBS device to lie flat under the scalp. The DBS device is switched offfor the first month, to allow the patients time to heal after the surgery and to test settings prior to the study.

A patient’s first in-person follow-up appointment takes place around four weeks after surgery, when the study team switch on and programme the device, with the aim of getting the stimulation settings right for that individual. The device will then be switched off again, until they attend their randomisation visit two months after surgery. At this visit, the participants will be shown how to manage their devices.

After another month, they will return so that the programme on the device can be changed to the other stimulation setting. Four months after the surgery, the device will be switched to the best ON setting and there is a further six months for testing advanced features and optimising the settings.

Professor Ben Seymour, of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, said: “It is exciting to see this study in progress. It promises to be a landmark study in pain therapeutics and neurotechnology, and builds on the considerable strength of Oxford functional neurosurgical and bioelectronics teams.

“Collaboration between clinicians and engineers is a key strategic goal at Oxford, and chronic pain is an area where there is considerable opportunity looking forward.”

A patient’s story

One of the first participants to undergo the procedure was Nigel Price, aged 58 from Bristol.

Nigel suffered a stroke in January 2022 while on a work video call. A few months afterward he started getting a tingling in his face: “That was just a couple of hours. The next day it lasted for seven hours and the day after it was just continuous. Eventually it was diagnosed as a central post stroke pain. I was told there was no cure. It was a bit of a shock, because by that time it had progressed, as though somebody was turning up a dial on the side of my head every single day.”

“Initially, it was like having really bad sunburn or having a nettle wiped around your eye. And that spread all down my left side – the side of my body affected by the stroke. It was gradually getting worse. If I just push my hand through the air, it stings. If I go out and it rains, it feels like someone’s sticking a dagger in my face.

Nigel spoke to his clinical team in Bristol and by luck, the person he spoke to had been part of Professor Green’s research team in Oxford and he was referred to the EPIONE study.

“I could see the direction my pain was taking, and it wasn’t getting any easier. So, when I first heard about deep brain stimulation I thought, ‘I’ll go and find out, but I’m absolutely not doing this’. But as time went on, I realised I couldn’t really control it with medication. I didn’t really have a plan B. It got to the point where it was becoming more and more disabling; walking became a lot harder for me; my social circle is sort of gone; I haven’t been able to return to work; I can’t drive. I’d come from thinking ‘I can beat this’ to thinking I haven’t got much choice.

“I was more confident than the rest of my family. People were saying ‘aren’t you brave?’ And I was thinking, ‘it would be braver trying to live with the pain, really’.

The device was activated briefly as part of the surgery, to test that the signals were working and that the research team could extract data from it. But for now, it will be switched off for two months. Nigel says he expects it to take a few months to fully recover from the surgery, both physically and emotionally. But he says that he experienced fatigue following his stroke anyway. His most pressing concern is avoiding infection.

“It’s going to be more a marathon than a sprint. But it does really feel like you’re right at the cutting edge of something. I’ve got so much confidence in them as a team. You’re in about the safest hands you could be for this type of operation.

“I actually felt incredibly lucky that the Oxford work was taking place because I didn’t have a plan B. You know there’s no cure. I’d gone down the medication route and pushed it as much as I could, but I didn’t really get any meaningful relief. And there are lots of side effects – you often turn into a complete zombie.

“When you look at other people who’ve got the condition, the one thing that a lot of them don’t have is hope, because they don’t think there is any solution available to them.

“The key word is hope. You can see from people’s posts on Facebook that they have reached a point where they have exhausted everything that they believe is available. Obviously, I want this to be a success for me, but also all the people to come because this isn’t going to stop. If eight percent of people who’ve had a stroke develop this pain, there must be a massive pool out there of people who are really struggling. I’ve obviously got a very personal interest, but I would be delighted if other people could benefit from it as well.”