An international study involving NIHR Oxford BRC researchers has shown where normal blood pressure in pregnancy should be across the world and when clinicians should react because it is abnormal.

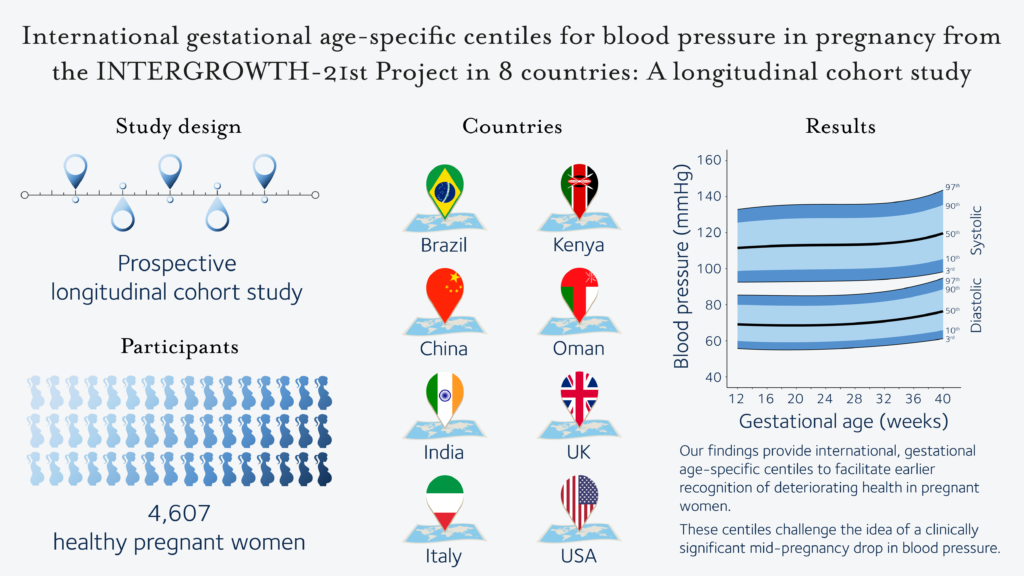

The study’s findings, published in PLOS Medicine, provide international, gestational age-specific centiles and limits of acceptable change to facilitate earlier recognition of deteriorating health in pregnant women.

“These centiles challenge the idea of a clinically significant mid-pregnancy drop in blood pressure,” said one of the authors, Prof Peter Watkinson, joint clinical lead for the Critical Care Research Group at the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences.

“We hope this international study will help to improve diagnosis of illnesses affecting blood pressure in pregnancy,” said Prof Watkinson, the Oxford BRC’s Joint Theme Lead for Technology and Digital Health.

The purpose of the study was to identify internationally applicable gestational age-specific centiles for blood pressure in clinical practice to determine when women have left the ‘normal’ range.

As part of the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st) Project, the research team recruited 4,607 healthy women across eight countries: Brazil, China, India, Italy, Kenya, Oman, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The researchers found that, on average, systolic blood pressure rose by around 8 mmHg (millimetres of mercury, the standard measurement for blood pressure) between 12 and 40 weeks’ gestation, with no decrease in mid-pregnancy. Diastolic blood pressure decreased slightly between 12 and 19 weeks, rising thereafter until 40 weeks’ gestation.

At any gestational age, systolic blood pressure fell by more than 14 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by more than 11 mmHg from baseline in fewer than 10% of women. Fewer than 10% of women increased their systolic blood pressure by more than 24 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure by more than 18 mmHg at any gestational age.