A new conjugate vaccine against typhoid has been proven in trials in Oxford to be safe and effective in preventing the disease, and can be used to protect both adults and children.

A study published in The Lancet is the first clinical trial to show that immunisation with a new vaccine called Vi-TT is safe, well tolerated and will have significant impact on disease incidence in typhoid endemic areas that introduce the vaccine.

The trial was led by University of Oxford Professor of Paediatric Infection and Immunity, Andrew Pollard, who is NIHR Oxford BRC Co-Theme Lead for Vaccines and is Director of the Oxford Vaccine Group.

The latest study was funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, building on previous investment from NIHR Oxford BRC and the Wellcome Trust. The BRC funded the initial work on the human challenge model six years ago.

The new vaccine has been submitted to the World Health Organisation (WHO) by Bharat Biotech of India Ltd for prequalification. This determines that the vaccine is safe and effective and can be procured by UNICEF for use in low-resource settings.

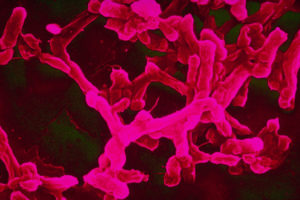

Typhoid is caused by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi, and is responsible for around 20 million new infections and 200,000 deaths each year, mainly in South and South East Asia and Africa.

The disease is associated with inadequate sanitation and contaminated drinking water, and common symptoms include fever, stomach pain, headache and constipation or diarrhoea.

Children are especially susceptible, but the currently licensed vaccines either come in inappropriate formats or do not confer lasting immunity in children.

“This new vaccine could be a real game changer in tackling a disease that disproportionately affects both poor people and children,” Prof Pollard (pictured left) said.

“This new vaccine could be a real game changer in tackling a disease that disproportionately affects both poor people and children,” Prof Pollard (pictured left) said.

“For the first time, we will be able to offer protection to children under two years of age, which will enable us to stem the tide of the disease in the countries where it claims the most lives.

“If we are going to make serious headway in tackling typhoid, we need to dramatically reduce the number of people suffering from and carrying the disease globally, which will in turn lead to fewer people being at risk of encountering the infection.”

He added: “This is a disease that only affects humans, and I believe that it will be possible for us to eradicate it one day. However, we’re currently losing ground, as overuse of antibiotics is leading to the emergence of new resistant strains, which are spreading rapidly.”

The researchers tested the vaccine at Oxford University using a controlled human infection model, which involved asking around 100 participants, many of whom were university students, to consume a drink containing the bacteria.

Human infection models have been used for hundreds of years to test vaccines, and are particularly useful in studying diseases for which no suitable animal model exists.

Human infection models can offer significant benefits, such as enabling researchers to test how effective vaccines are against specific pathogens, or identifying targets for new vaccines by observing how the body mounts a protective immune response.

After the success of this trial, the researchers are now looking to expand infection models to new settings and locations.