A second person has experienced sustained remission from HIV-1 after ceasing treatment, ten years after the first such case.

The case was reported in a paper to be published in Nature. Like the first such case, known as the ‘Berlin Patient’, the second patient was treated with stem cell transplants from donors carrying a genetic mutation that prevents expression of the HIV receptor CCR5.

The subject of the new study has been in remission for 18 months after his antiretroviral therapy (ARV) was discontinued. The authors say it is too early to say with certainty that he has been cured of HIV, and will continue to monitor his condition.

The study, led by researchers at UCL and Imperial College London and involving teams from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, was carried out as part of the CHERUB collaboration, involving five leading NIHR Biomedical Research Centres: Imperial, UCL, King’s, Cambridge and Oxford.

“At the moment the only way to treat HIV is with medications that suppress the virus, which people need to take for their entire lives, posing a particular challenge in developing countries,” said the study’s lead author, Professor Ravindra Gupta (UCL, UCLH and University of Cambridge).

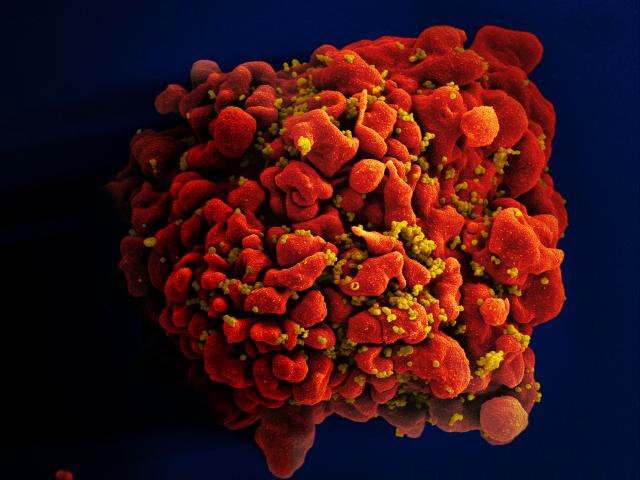

“Finding a way to eliminate the virus entirely is an urgent global priority, but is particularly difficult because the virus integrates into the white blood cells of its host.”

Close to 37 million people are living with HIV worldwide, but only 59% are receiving ARV, and drug-resistant HIV is a growing concern. According to the World Health Organisation, almost one million people die each year from HIV-related causes.

The report describes an anonymous male patient in the UK, who was diagnosed with HIV infection in 2003 and who was on ARV therapy since 2012.

Later in 2012, he was diagnosed with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In addition to chemotherapy, he underwent a haematopoietic stem cell transplant from a donor with two copies of the CCR5 Δ32 allele in 2016.

CCR5 is the most commonly used receptor by HIV-1. People who have two mutated copies of the CCR5 allele are resistant to the HIV-1 virus strain that uses this receptor, as the virus cannot enter host cells.

Chemotherapy can be effective against HIV as it kills cells that are dividing. Replacing immune cells with those that don’t have the CCR5 receptor appears to be key in preventing HIV from rebounding after the treatment.

The transplant was relatively uncomplicated, but with some side-effects, including mild graft-versus-host disease, a complication of transplants wherein the donor immune cells attack the recipient’s immune cells.

The patient remained on ARV for 16 months after the transplant, at which point the clinical team and the patient decided to interrupt ARV therapy to test if the patient was truly in HIV-1 remission.

Regular testing confirmed that the patient’s viral load remained undetectable, and he has been in remission for 18 months since ceasing ARV therapy – and 35 months post-transplant. The patient’s immune cells remain unable to express the CCR5 receptor.

He is only the second person documented to be in sustained remission without ARV. The first, the Berlin Patient, also received a stem cell transplant from a donor with two CCR5 Δ32 alleles, but to treat leukaemia.

Notable differences were that the Berlin Patient was given two transplants, and underwent total body irradiation, while the UK patient received just one transplant and less intensive chemotherapy.

Both patients experienced mild graft-versus-host disease, which may also have played a role in the loss of HIV-infected cells.

As well as having a leading role in CHERUB, Oxford carried out some of the assays in this trial to show there was no evidence of persisting virus.

“By achieving remission in a second patient using a similar approach, we have shown that the Berlin Patient was not an anomaly, and that it really was the treatment approaches that eliminated HIV in these two people,” said Prof Gupta.

The researchers caution that the approach is not appropriate as a standard HIV treatment due to the toxicity of chemotherapy, but it offers hope for new treatment strategies that might eliminate HIV altogether.

“Continuing our research, we need to understand if we could knock out this receptor in people with HIV, which may be possible with gene therapy,” said Professor Gupta.

“The treatment we used was different from that used on the Berlin Patient, because it did not involve radiotherapy. Its effectiveness underlines the importance of developing new strategies based on preventing CCR5 expression,” said co-author Dr Ian Gabriel (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust).

“While it is too early to say with certainty that our patient is now cured of HIV, and doctors will continue to monitor his condition, the apparent success of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation offers hope in the search for a long-awaited cure for HIV/AIDS,” said Professor Eduardo Olavarria (Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London).

As well as the BRCs, the research was funded by Wellcome, the Medical Research Council and the Foundation for AIDS Research.