New national guidelines are recommending that all babies born with Down’s syndrome should have a new genetic test to detect signs of a potentially fatal preleukaemic condition, following research by a University of Oxford group led by NIHR Oxford BRC-supported investigators.

New national guidelines are recommending that all babies born with Down’s syndrome should have a new genetic test to detect signs of a potentially fatal preleukaemic condition, following research by a University of Oxford group led by NIHR Oxford BRC-supported investigators.

The new British Society for Haematology (BSH) guidelines, published in the British Journal of Haematology, are the result of years of research and clinical studies funded by the charities Bloodwise and Children with Cancer UK.

The research group was led by Prof Irene Roberts (Department of Paediatrics) and Prof Paresh Vyas, the Oxford BRC’s Co-theme Lead for Haematology, both of whom work at the MRC Molecular Haematology Unit, based at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine.

The recommendations are that all babies with Down’s syndrome should have a blood count and blood film in the first few days of life. Early intervention will greatly increase the chances of survival for children who develop symptoms.

The test can be done at the same time as other blood tests, and in most cases, will mean that parents can be reassured. In those cases where the results of these test alert the clinical team of a potential diagnosis, a further genetic test will be conducted, and monitoring will take place to check for any signs of progression into leukaemia.

Saving lives

“Until now guidelines for the treatment of children with Down syndrome at risk of developing leukaemia have been vague, implementation has been haphazard and children have been diagnosed late as a result,” said Prof Roberts.

“Early intervention greatly increases children’s chances of survival if symptoms do develop, helping to save lives.”

Prof Vyas (left) added: “A simple test can ensure that those children at risk of cancer are put under the care of a specialist paediatrician, they are properly monitored and are treated straight away when symptoms develop. Importantly, it also provides reassurance to the parents of those children not at risk, removing the fear and worry of leukaemia for many families.”

Prof Vyas (left) added: “A simple test can ensure that those children at risk of cancer are put under the care of a specialist paediatrician, they are properly monitored and are treated straight away when symptoms develop. Importantly, it also provides reassurance to the parents of those children not at risk, removing the fear and worry of leukaemia for many families.”

The new clinical guidelines are the result of years of research and clinical studies funded by the charities Bloodwise and Children with Cancer UK.

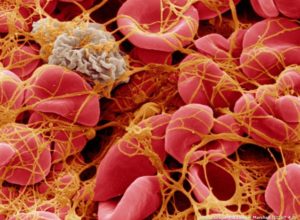

Children with Down’s syndrome have a one in 50 chance of developing acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), compared to a one in 7,000 chance for children without Down’s syndrome.

Around one in 10 children with Down’s syndrome are born with a pre-leukaemic condition known as Transient Leukaemia of Down syndrome’ (TL-DS). This condition, also sometimes called ‘TAM’, can develop into Acute Myeloid Leukaemia of Down Syndrome (ML-DS) in one in five cases.

Risks

TL-DS itself carries significant risks, with up to one in five children with the severe form dying within six months of diagnosis as a result of the condition – most commonly from liver dysfunction. Mutations to the GATA1 gene, which is important to healthy blood production, are found in both TL-DS and ML-DS in children with Down’s syndrome.

The new clinical guidelines recommend that a full blood count, which measures levels of different types of blood cell, is taken within three days of birth in children with Down’s syndrome. These newborns should also be examined for signs of TL-DS, which include organ enlargement, liver dysfunction and skin rashes.

If blood counts reveal that there are high levels of immature ‘blast’ cells in the bloodstream and there are physical symptoms, babies should be screened for the GATA1 mutation to determine if they have TL-DS – a test that was developed by the Oxford group.

The outcome for children with TL-DS who develop severe liver dysfunction and other complications is significantly improved by early intervention. The new guidelines recommend that all babies confirmed as having TL-DS are monitored regularly and children who develop life-threatening symptoms should be given low-dose chemotherapy immediately.