A team of Oxford researchers has discovered a link between immune cells known as monocytes in tumours and overall survival in patients with oesophageal cancer.

A study by Ludwig Cancer Research, supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) found that the presence of relatively high numbers of monocytes in tumours was linked to better outcomes in oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC) patients treated with a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, or immunochemotherapy.

The results also applied to the most common forms of gastric cancer, indicating potential for future research.

The study was led by Ludwig Oxford Director Xin Lu, the Oxford BRC’s Theme Lead for Cancer, and former graduate student Thomas Carroll and published in the journal Cancer Cell.

It showed that tumour mutational burden (TMB) – the degree to which a tumour’s malignant cells are mutated – also predicted survival outcomes.

Furthermore, combining TMB and tumour monocyte content (TMC) was even more effective at predicting treatment response than either measurement alone. This suggests that the combined measurement is a potential biomarker for the selection of patients likely to benefit from immunochemotherapy.

Oesophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, and the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma has been climbing steadily over the past 40 years. Survival times for inoperable or metastatic forms of the cancer range from six to 12 months.

“Some cancer patients respond to treatment while some do not, and still others respond only partially,” said Lu. “The challenge is to understand why certain people fall into each category and identify the molecular bases of their heterogeneous responses.”

The clinical trial was launched in 2015 by Ludwig Oxford. The 35 patients with inoperable oesophageal adenocarcinoma enrolled in this trial, unlike those in many others, received four weeks of immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) before undergoing 18 weeks of combination immunochemotherapy.

ICIs are a type of immunotherapy drug that blocks proteins that stop the immune system from attacking the cancer cells.

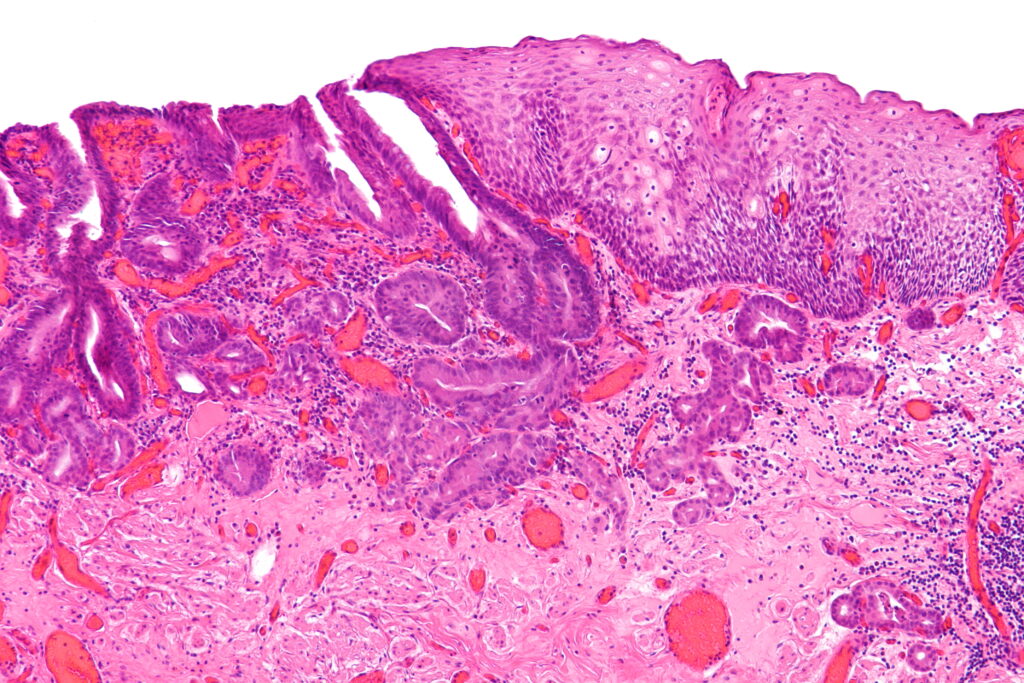

Both healthy and cancerous biopsies were collected from the patients at multiple time points and from multiple sites over the course of their treatment. The researchers then performed single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on 65,000 cells from a subset of the clinical trial patients to generate a detailed cellular atlas of the upper gastrointestinal tract, which served as a reference map of all the cell types that can be found in oesophageal cancers.

Due to technical and other challenges associated with scRNA-seq—which analyses the RNA output of individual cells—such analysis was only performed on eight of the 35 patients in the trial. However, the biopsies of all patients underwent more cost-effective bulk RNA sequencing.

The team then used computational methods—deconvolution algorithms—to determine with high confidence the proportion of different cell types in each biopsy. Deconvolution is a computational tool that combines the biological insights from scRNA and bulk RNA sequencing while compensating for the particular weaknesses of each method—high cost and low resolution, respectively.

“In clinical research, we have to find ways to get as much information as possible from each precious sample. In this case, we wanted to use single-cell sequencing on a subset of those samples to gain detailed insight into the cell composition of these tumours, and combine that knowledge with the statistical power of conducting bulk RNA sequencing on everyone. That’s what deconvolution attempts to do,” Carroll explained.

Deconvolution revealed that the number of monocytes in the tumour before treatment was the most reliable predictor of outcome. This finding was surprising because ICI primarily targets the immune system’s T cells, which lead the assault on tumours.

“We found that pre-treatment T cell markers are not at all useful in predicting long-term patient outcomes for the treatment used in this trial,” Carroll said.

The researchers hypothesise that the patients with high TMC can generate more pro-inflammatory immune cells from the monocytes in response to ICI therapy than patients with low TMC. Supporting this, they found that after four weeks of ICI, TMC-high patients showed a higher level of dendritic cells and M1 macrophages, which elicit pro-inflammatory or “tumour-killing” responses, while TMC-low patients had more anti-inflammatory or “tumour-supporting” M2 macrophages.

“We don’t have the formal demonstration of this yet, and that’s where the future research will be,” Lu said.

Using publicly available data, the team also confirmed that the link between high TMC and improved outcomes held for the most common forms of gastric cancer as well.

Aside from identifying the combination of TMB and TMC as potential biomarkers for response to immunochemotherapy, the researchers report that expression of PD-L1, a protein targeted by ICI in the clinical trial, is not a good predictor of patient outcomes for such therapies.

They also identify a novel T cell inflammation signature (INCITE) that correlates with ICI-induced tumour shrinkage. This signature could serve as a general indicator of a patient’s responsiveness to immunotherapy, irrespective of their cancer.