A clinical trial has shown that a three-month rapid weight loss programme was not only safe but also effective in reducing the severity of a liver disease called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with liver fibrosis.

Results of the trial, which showed that improvements were maintained beyond the end of the diet, have been published in the journal Obesity.

Typically, in this advanced type of liver disease, there is inflammation and scarring in the liver caused by a build-up of fat. NASH with liver fibrosis, which is estimated to affect up to two percent of adults worldwide, can lead to liver cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Currently, no medication has been approved for this condition, so advice to lose weight is the mainstay of treatment. In most cases, however, this leads to only modest weight loss.

Rapid weight loss programmes through ‘soups and shakes’ have been shown to be effective for treating obesity and type 2 diabetes. However, they are not routinely used in people with NASH with liver fibrosis because of safety concerns.

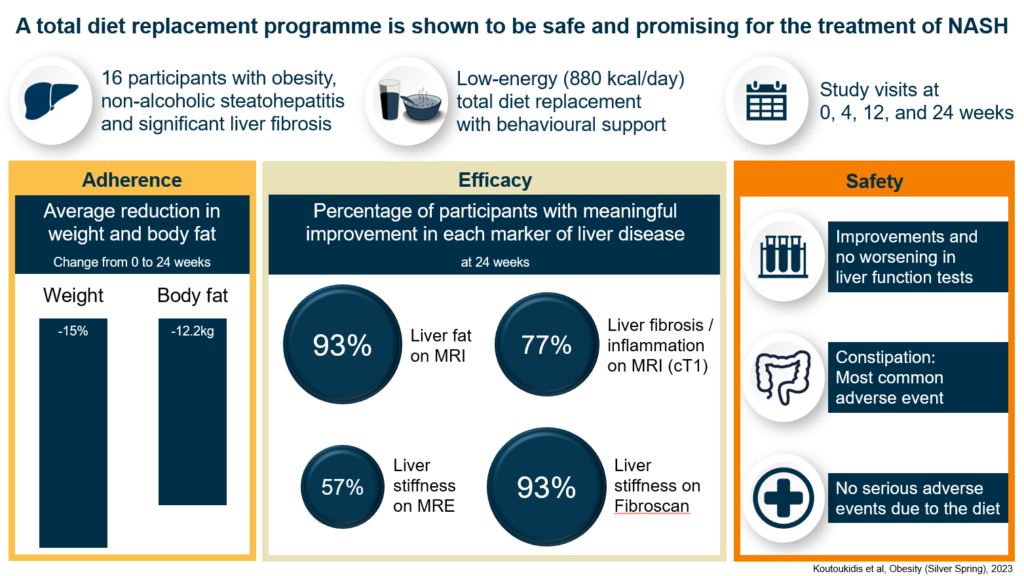

In the trial by a team from the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), 16 people with obesity, NASH and moderate to advanced liver fibrosis took part in a weight loss programme; they replaced all their regular food with specially formulated and nutritious soups, shakes and bars for 12 weeks.

Over the following 12 weeks, they gradually re-introduced regular food to their diet. Throughout the 24 weeks, they received regular support from a dietitian to keep them on track and motivated.

At the start of the trial, participants had blood tests, their weight and blood pressure taken, and scans that measure the health of the liver. These were repeated after 12 and 24 weeks.

Fourteen participants completed the study and on average they lost 15 percent of their bodyweight, indicating that they largely stuck to the weight loss programme.

Tests also revealed that liver function had significantly improved, and there had been no serious adverse events related to the weight loss programme. The scans also showed that most participants had clinically meaningful improvements in their liver markers. These were some of the largest improvements reported in the literature, approaching those seen with larger weight loss after bariatric surgery, and no medication has shown a larger improvement.

In addition, markers that indicate a risk of developing heart disease, including blood pressure and a measure of blood sugar levels, also significantly improved. Participants who had hypertension or type 2 diabetes at the initial visit were also able to reduce their medication to control these conditions.

This highlights the potential of the rapid weight loss programme to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, the most common cause of death in this population, and reliance on certain medications.

“We are delighted with the exciting results we have seen. This was a small study, and this approach will need to be tested in a larger randomised controlled trial. But our results show that rapid and well-supervised weight loss has the potential to reverse the progression of liver disease,” said Dimitrios Koutoukidis, Senior Research Fellow at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences and lead author of the paper.

“We hope that this research will prompt a change in routine liver clinics and allow more frequent use of similar weight loss programmes, especially as no medication has so far been shown to be effective.

“The outstanding outcome we have seen would not have been possible without the contribution of those who took part in this trial, whom we’d like to thank.”