The results of a first-in-human clinical trial of gene therapy to treat a common cause of genetic blindness have shown partial reversal of sight loss in some patients.

X-linked retinitis pigmentosa, caused by mutations in RPGR gene, is the most common cause of blindness in young people. The inherited mutations lead to degeneration of light sensitive cells (photoreceptors) beginning in early childhood leading to severe sight loss.

Until now there has been no treatment for this disease. Gene therapy using viral vectors to deliver a healthy copy of a mutated gene into affected cells aims to slow down the degeneration and preserve visual function.

However, the RPGR gene has an unusual genetic code which makes it unstable to work with in the laboratory and until now difficult to translate into human trials.

Scientists at the University of Oxford reprogrammed the genetic code of the RPGR gene to make it more stable, providing the basis for this first-in-human retinal gene therapy.

The international trial, led by Professor Robert MacLaren, was sponsored by Biogen Inc., with support from the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Eighteen patients in total were treated with increasing doses of the vector carrying an RPGR gene in which the DNA had been altered, but in a manner that still allowed correct production of the missing protein.

Other trial sites included the Manchester Royal Eye Infirmary and the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami.

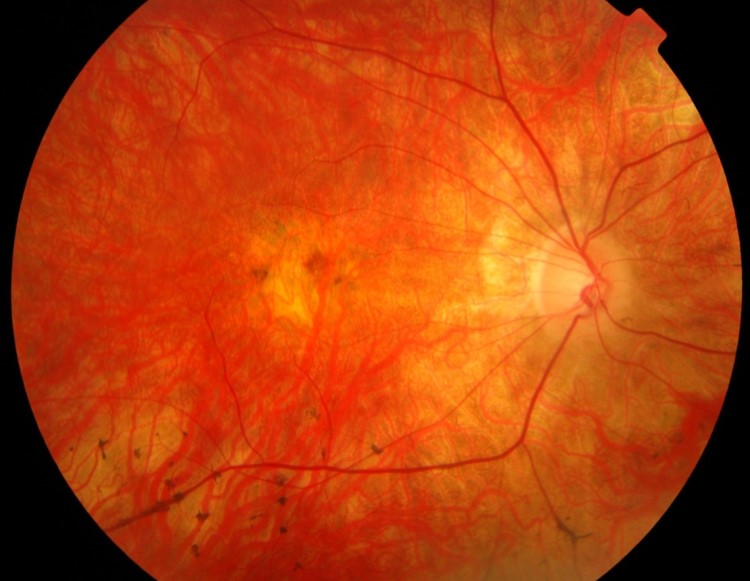

the eye of the patient

The research team’s findings are published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Prof MacLaren, Consultant Ophthalmologist at the Oxford Eye Hospital, commented: “We are delighted with the early results of this clinical trial for a degenerative eye disease. It is becoming more apparent to us that novel genetic therapies, when working, lead to a clear improvement in neuronal function, which holds great hope for a variety of other degenerative conditions that have a genetic basis.

“Once again, we should take note that this highly successful international gene therapy clinical trial originated in the NHS by applying science that was previously developed in a project funded in the UK by the Medical Research Council.”

The early results from the study showed that the treatment was safe and six patients who received mid doses of the vector had unexpected improvements in their peripheral vision beginning as early as one month after the treatment.

One of Prof MacLaren’s patients, Kurtis Lonie, said: “When my mum spotted the trial in an RNIB newsletter I felt so hopeful about what I was reading. At this stage in my life I was struggling deeply with what I thought my life would become. The speed of my condition’s degeneration was unknown so I had no choice but to apply and do whatever I could to hopefully help others in the future, as well as myself.

After undergoing tests and screening, Kurtis was given the choice of which eye he wanted to be treated, and he opted for the one with worse vision.

“About a month after the treatment my vision was beginning to return in the treated eye. The sharpness and depth of colours I was slowly beginning to see were so clear and attractive. My visual field exploded and I could see so much more at once than ever before in that eye. Before long, the eye was undoubtedly better than the untreated eye.

“The results have been nothing short of astonishing and life changing for me, I really hope this trial is approved and they can treat what once was my better eye.”

This improvement in peripheral vision experienced by some patients is believed to relate to regeneration of outer retinal structures following successful gene therapy and has implications for the development of similar gene-based treatments for many other retinal degenerations.

Nightstar Therapeutics was a University of Oxford spinout company founded in 2014 and listed on NASDAQ in 2017. The RPGR gene therapy developed in Oxford was licenced to Nightstar in order to set up the international clinical trial.

In 2018 Nightstar Therapeutics was acquired by the large US biotech company Biogen, in what was one of the biggest buyouts of a British biotechnology company to date.

The funding raised combined with the successful start of the clinical trial has highlighted the huge potential for academic collaborations between UK universities, the Department of Health and the global biotechnology sector. This has been a key long term strategic aim of the NHS funding directed through the National Institute for Health care Research (NIHR).