An injectable cure for inherited heart muscle conditions that can kill young people in the prime of their lives could be available within a few years, after an international team of researchers were announced as the winners of the British Heart Foundation’s (BHF) Big Beat Challenge.

The BHF award – at £30m, one of the largest non-commercial grants ever given – aims to help researchers rewrite DNA, in what is being described as a “defining moment” for cardiovascular medicine

The winning research team, CureHeart, is jointly let by the University of Oxford’s Professor Hugh Watkins, the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre’s (BRC) Theme Lead for Genomic Medicine.

It will seek to develop the first cures for inherited heart muscle diseases by pioneering revolutionary and ultra-precise gene therapy technologies that could edit or silence the faulty genes that cause these deadly conditions.

Professor Watkins, from the University’s Radcliffe Department of Medicine and lead investigator of CureHeart, said: “This is our once-in-generation opportunity to relieve families of the constant worry of sudden death, heart failure and potential need for a heart transplant. After 30 years of research, we have discovered many of the genes and specific genetic faults responsible for different cardiomyopathies, and how they work. We believe that we will have a gene therapy ready to start testing in clinical trials in the next five years.

“The £30 million from the BHF’s Big Beat Challenge will give us the platform to turbo-charge our progress in finding a cure so the next generation of children diagnosed with genetic cardiomyopathies can live long, happy and productive lives.”

The team, made up of world-leading scientists from the UK, US and Singapore, were selected by an International Advisory Panel chaired by Professor Sir Patrick Vallance, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK Government.

Professor Keith Channon, Head of the Radcliffe Department of Medicine, said: “I am delighted that the BHF have chosen the CureHeart team to deliver on this world-leading challenge. The Radcliffe Department of Medicine looks forward to supporting and fostering the collaborations between scientists and researchers from many disciplines who will be key to the success of the Cure Heart programme.”

Professor Gavin Screaton, Head of the University of Oxford’s Medical Sciences Division, commented: “This is an extraordinary opportunity for the CureHeart team to make a difference in the lives of so many patients across the world. We have a long history of multidisciplinary working here in the Medical Sciences Division, and pride ourselves in the many successes our scientists have had in translating their cutting-edge lab research into real life treatments. This work by Professor Watkins and the international CureHeart team exemplifies this ethic at its best and we are truly excited to see their progress.”

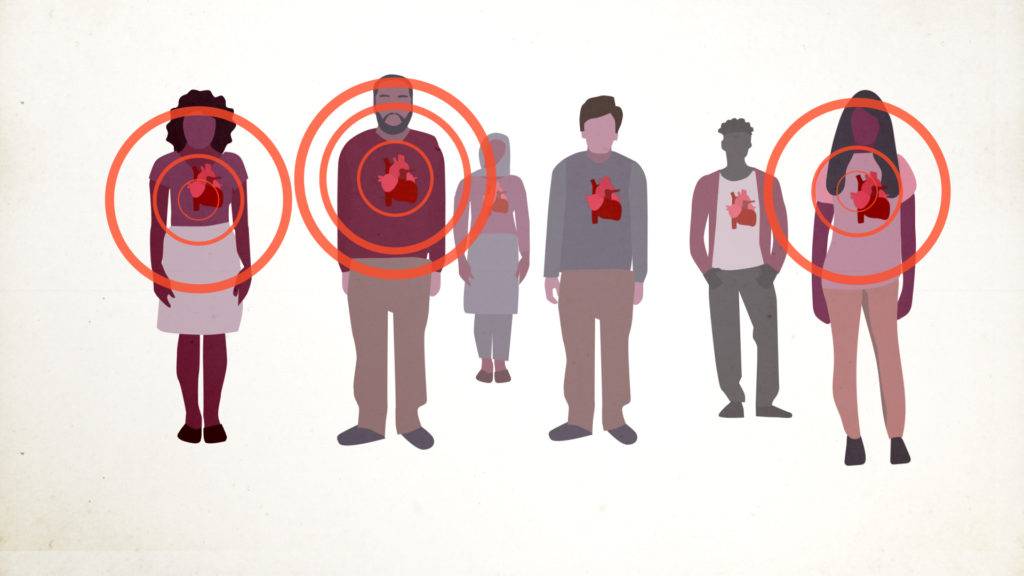

Inherited heart muscle diseases can cause the heart to stop suddenly or cause progressive heart failure in young people. Every week in the UK, 12 people under the age of 35 die of an undiagnosed heart condition, very often caused by one of these inherited heart muscle diseases, also known as genetic cardiomyopathies. Around half of all heart transplants are needed because of cardiomyopathy and current treatments do not prevent the condition from progressing.

It is estimated that one in 250 people worldwide – around 260,000 people in the UK – are affected by genetic cardiomyopathies, with a 50:50 risk they will pass their faulty genes on to each of their children. In many cases, multiple members of the same family will develop heart failure, need a heart transplant, or are lost to sudden cardiac death at a young age.

The team will take the revolutionary gene-editing technology of CRISPR to the next level by deploying ultra-precise techniques called base and prime editing in the heart for the first time. These ground-breaking approaches use ingenious molecules that act like tiny pencils to rewrite the single mutations that are buried within the DNA of heart cells in people with genetic cardiomyopathies.

They will focus this technology on two areas. First, where the faulty gene produces an abnormal protein in the pumping machinery of the heart, the team will aim to correct or silence the faulty gene by rewriting the single spelling mistakes or switching off the entire copy of the faulty gene.

Second, where the faulty gene does not produce enough protein for the heart muscle to work as it should, the team plan to increase the production of healthy heart muscle proteins by using genetic tools to correct the function of the faulty copy of the gene or to stimulate the normal copy of the gene.

These approaches have been shown to be successful in animals with cardiomyopathies and in human cells. The team believe the therapies could be delivered through an injection in the arm that would stop progression and potentially cure those already living with genetic cardiomyopathies. It could also prevent the disease developing in family members who carry a faulty gene but have not yet developed the condition.

Dr Christine Seidman at Harvard University and co-lead of CureHeart, said: “Acting on our mission will be a truly global effort. We’ve brought in pioneers in new, ultra-precise gene editing, and experts with the techniques to ensure we get our genetic tools straight into the heart safely. It’s because of our world-leading team from three different continents that our initial dream should become reality.”

Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, Medical Director at the British Heart Foundation, said: “This is a defining moment for cardiovascular medicine. Not only could CureHeart be the creators of the first cure for inherited heart muscle diseases by tackling killer genes that run through family trees, it could also usher in a new era of precision cardiology. Once successful, the same gene editing innovations could be used to treat a whole range of common heart conditions where genetic faults play a major role. This would have a transformational impact and offer hope to the thousands of families worldwide affected by these devastating diseases.”

Sir Patrick Vallance, Chair of the BHF’s International Advisory Panel and Government Chief Scientific Adviser, said: “CureHeart was selected in recognition of the boldness of its ambition, the scale of its potential benefit for patients with genetic heart muscle diseases and their families, and the excellence of the international team of participating researchers.”

Dr Charmaine Griffiths, Chief Executive of the British Heart Foundation, said: “With the public’s support, the aim of the Big Beat Challenge was to move past incremental progress and make a giant leap in an important area of heart patient care. Creating the world’s first genetic cure for a heart disease would undoubtedly do this and has the potential to stop families losing loved ones without a moment’s notice to these cruel diseases. However, we need the continued backing of our supporters to turn science like this into a reality for the millions of people around the world living with heart disease.”

Patient story – Max Jarmey, 27

Max Jarmey was just 13 when his dad Chris died suddenly following a cardiac arrest, caused by a condition called arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC, a type of genetic cardiomyopathy).

A few years later Max was told that he had ARVC (which is now known as arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy) following a routine screening appointment. Shortly after, his younger brother Tom was also diagnosed. Both had inherited the condition from their dad.

Max describes himself as “obsessed with sport” growing up and he competed in mountain biking to a high level until 18, when his diagnosis meant he had to give it up.

He said: “I’m pretty mentally robust but the first six months following my diagnosis were incredibly difficult. It was horrible to be told I had a condition like ARVC at the age I was told, and then to be forced to quit something I loved.”

Now 27, Max tries to focus on what he can do rather than what his condition stops him doing. He has been fitted with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), which has shocked his heart back into a normal rhythm after it’s gone into a life-threatening rhythm – protecting him from a cardiac arrest – many times over the years

Max said: “I think the only way to deal with my ARVC is to accept it and the fact that I can’t control it. If I dwelt on it every day would be hard, but I do think about it often.”

Professor Watkins (pictured left) diagnosed Max and has been his cardiologist ever since. Max said: “When Hugh told me about CureHeart I knew I wanted to be involved with something so inspiring. When I think about my future, the decision to have children and their future, CureHeart could make that decision easier. My children might never have to suffer like I have with this condition. That is completely life changing.

“This project gives me hope. That’s what the BHF is funding – hope. This is not just about managing symptoms. CureHeart could be the cure for genetic cardiomyopathies.”